News

TNB, a 70-year chequered history in electricity supply

By Yong Soo Heong

KUALA LUMPUR, Sept 1 -- If one were to delve into the chequered history of Tenaga Nasional Bhd (TNB), colourful stories of its early beginnings, rivalries between various arms of the colonial administration, what constituted to be of utmost priority, long debates on the best mode of electrification and how decisions were made would come to the fore.

One would even find that palm oil was already in use as an alternative fuel source when diesel was hard to come by some 70 years ago, that coconut oil was used a lubricant for power generators during hard times and that “independent power producers” (IPPs) were already in existence in Malaya before World War II as the exigencies of a growing economy, especially in tin mining, demanded such commercial arrangements. These developments provide a valuable insight into the ingenuity of humans as the use of palm oil as fuel and the need for IPPs are still relevant in the 21st century!

It would be pertinent to mention that during the dark days of the Japanese Occupation (Dec 8,1941, to September 1945), civilian engineers from Japan worked feverishly together with the local workforce to restore almost 80 per cent of the electricity power installations abandoned or destroyed by the retreating British forces. This earned the respect of many locals that the Japanese heads of local power stations run by Nippon Hassoden Kabushiki Kaisha (NHKK) were even affectionately known as “Tuan Api”!

The above examples showed that electricity was one of the greatest discoveries of science and technology, a boon to mankind and a vital ingredient for development, starting from the late 19th century until now. In that, Malaysia spared no effort to ensure that electricity lights up our lives, every time.

A two-volume book -- “Power Builds the Nation” – written by the late London-born Muzaffar (Desmond) Tate commissioned by the National Electricity Board (NEB), the predecessor of TNB, on its 40th anniversary in 1989, provides much insight into the establishment of one of Malaysia’s best-known public utilities and companies.

“Most people take electricity for granted. This book shows why it should not be,” Tate wrote as he traced the development of electricity supply in the country during the colonial period before the Second World War (WW II), especially the development of electricity supply in Kuala Lumpur, which provided the nucleus from which TNB eventually evolved.

Tate also touched on the supply of electricity to other parts of the country, in particular the formation and growth of the Perak River Hydro-Electric Power Company (and its subsidiary, Kinta Electrical Distribution Company), which was the largest generator of electricity in Peninsula Malaya prior to WW II.

In his book, readers can also find out in greater detail on the personalities behind certain road names in the country like Stonor, Cochrane, Belfield, Hose, Robson, Young, Watson and Treacher, to name a few.

Interestingly, Tate’s book also throws some light on how the Japanese Occupation had affected local electrical engineers and technicians in that it gave them “a new confidence engendered by successfully handling tasks for which before the war had been the preserve of (British) expatriate engineers.”

It tells how that under Japanese direction, the local workforce had on their own resources succeeded in rehabilitating plants damaged by the departing British.

The experiences of A. Ramanath, NEB’s Deputy General Manager (Planning and Construction) in the 1980s, provide a valuable insight of the war years in that the Japanese made local engineers and technicians manifest their competence and made it clear that there was nothing mystical in power station engineering in that it was just hard work and a proper understanding of the technology involved.

In his own words contained in another NEB book, “People Behind the Lights”, he said the contribution of the Japanese in upgrading the engineering capability of the local engineers was often not told or appreciated.

Ramanath wrote: ”When the British left Malaya in early 1942, they carried out a denial policy in the power stations – allowing fires to burn full blast and then letting the boilers melt down by shutting off the water supply, and dismantling turbines and destroying critical parts.

“At the Bangsar power station, these important components were dumped into the cooling ponds. When the Japanese came, the Japanese manager for the power station, together with local engineers and technical assistants got the parts together from spares and scrap, and the power station was able to start supplying electricity to Kuala Lumpur within one month.”

Thus it was with this new self-confidence and a more independent outlook resulting from the experiences during the war where Malaysians, who had manned electricity installations of the country, met up again with the British after the war was over. But the British were viewed in different light this time around.

The period after WW II was marked by efforts to rehabilitate power stations that had been damaged earlier. Demand for power in Peninsula Malaysia exceeded supply. The Electricity Department of the colonial administration, which was responsible for this task, tried to satisfy all classes of consumers, from government installations to businesses and to homes. The aftermath of the war made it difficult to procure parts and get supply up and running quickly.

For example, in an effort to boost power supply, the Electricity Department ordered a 30-tonne boiler which came on board an aircraft carrier that was off-loaded at Port Swettenham (now Port Klang).

In view of its large size, the department had to borrow a carrier truck used for transporting huge Sherman tanks from the British Army to transport the boiler. To avoid sharp bends and weak bridges from the port to Kuala Lumpur, it took on a circuitous route that included rural areas.

Unfortunately, when the truck was nearing then rural Puchong (as opposed a now bustling township), the soft road table there gave way and the boiler slowly sank into an adjacent padi field. It took two weeks for the boiler to be extricated from the mud before it made its way to the Bangsar power station.

In 1948, with the rehabilitation of power supply somewhat fully completed, a proposal to set up the Central Electricity Board (CEB), the forerunner of NEB and TNB, was set in motion.

The authorities felt that it was best to leave the responsibility of generating electricity to a statutory body or commercial entity rather than a government department. The principal object was to establish an autonomous organisation to be the sole authority in unifying and controlling the generation, supply and use of electricity.

On Sept 1, 1949, CEB came into existence to herald a new era of electricity supply in the country. Much water has flowed under the bridge since then, with CEB being renamed NEB on June 22, 1965.

On Sept 1, 1990, Tun Dr Mahathir Mohamad, who was the country’s fourth prime minister then, officially proclaimed TNB as the heir and successor to NEB.

In the words of the late Tan Sri Dr Ani Arope, TNB’s first chairman, TNB has been a remarkable and inspiring story about how Malaysians had successfully taken over from and expanded an enterprise which had started under the former British colonial regime. The rest is history as today TNB has grown to be among one of the better-run power utilities in the world.

-- BERNAMA

Other News

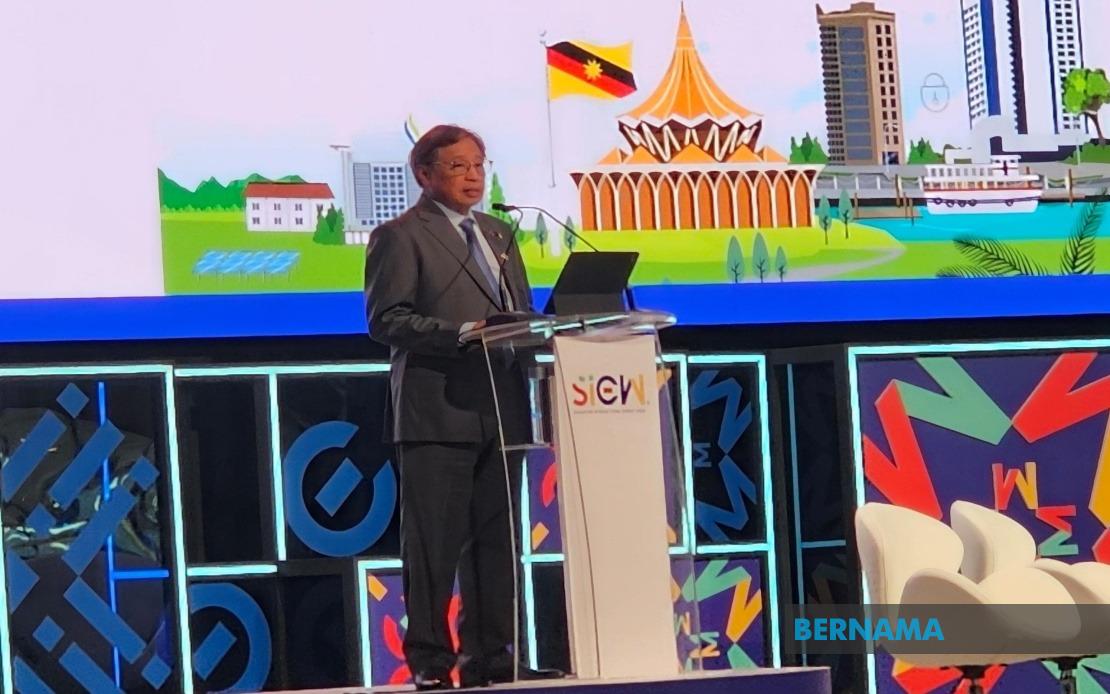

Sarawak Lepasi Sasaran Kapasiti Gabungan Tenaga Boleh Baharu Tahun Ini - Abang Johari

Oleh Nur Ashikin Abdul Aziz

SINGAPURA, 21 Okt (Bernama) -- Sarawak mencapai 62 peratus sasaran campuran kapasiti tenaga boleh baharu (TBB) tahun ini, melepasi sasaran 60 peratus yang digariskan dalam Strategi Pembangunan Pasca COVID-19 (PCDS) 2030.

Sarawak Pacu Pertumbuhan Tenaga Boleh Diperbaharui Untuk Manfaat ASEAN - Premier

SINGAPURA, 21 Okt (Bernama) -- Sarawak komited menyokong peralihan tenaga boleh diperbaharui di Asia Tenggara dengan memanfaatkan potensinya sebagai "Bateri ASEAN," yang akan membekalkan tenaga bersih menerusi sambungan Grid Kuasa Borneo dan ASEAN.

Belanjawan 2025 Percepat Peralihan Kepada Tenaga Bersih - Solarvest

KUALA LUMPUR, 19 Okt (Bernama) -- Belanjawan 2025 merupakan satu langkah ke arah mempercepat peralihan kepada tenaga bersih di Malaysia, kata Solarvest Holdings Bhd.

© 2025 BERNAMA. All Rights Reserved.

Disclaimer | Privacy Policy | Security Policy This material may not be published, broadcast,

rewritten or redistributed in any form except with the prior written permission of BERNAMA.

Contact us :

General [ +603-2693 9933, helpdesk@bernama.com ]

Product/Service Enquiries [ +603-2050 4466, digitalsales@bernama.com ]